In many ways, the European outlook is like other advanced economies. Strong growth this year is set to return closer to trend as the reopening boost fades, whilst high inflation should fall back as transitory supply‑demand imbalances ease. But a key differentiating factor is that rate hikes remain far off due to the outcome of ECB’s strategy review which has set a high bar for tightening. Also, varying vaccination rates mean the bloc is particularly susceptible to any risks posed by the new Omicron strain, bringing with it an increased likelihood of further lockdowns.

A winter of discontent is coming

After flatlining in Q1, the eurozone recovery has gained pace with sequential GDP growth exceeding 2% in both Q2 and Q3. A key factor underpinning this was the recovery in global trade, which provided a notable boost to the export‑oriented industrial sector, as was the rollout of vaccines that allowed governments to ease constraints on social activities. But beyond the healthy headline picture, southern states have lagged their northern neighbours. This largely reflects the significance of tourism to their economies, which was hampered by continued weakness in international travel in the summer.

While growth should go on to moderate next year, there will be a few supporting factors. An easing in supply bottlenecks would enable manufacturers to restock, whereas less stringent travel rules should boost tourism. However, low vaccination rates in some countries have caused another wave of cases to spread across the continent. This has led to a tightening of restrictions in several countries which has sparked large‑scale, violent protests. Forecasters look for growth to moderate from 5.1% this year to 4.2% in 2022. However, the emergence of the Omicron variant increases the likelihood of a widespread reimposition of restrictions that could dampen growth in late-2021 and early-2022.

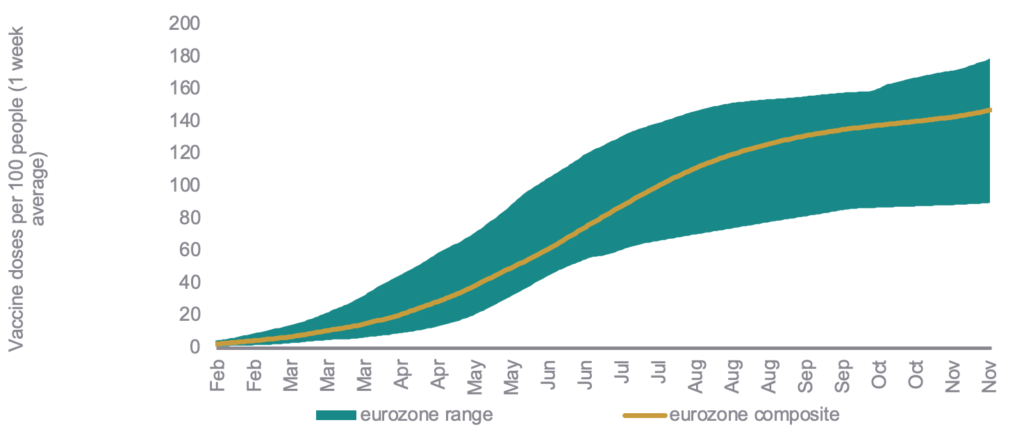

Vaccination rates vary considerably in the eurozone

We construct the eurozone composite by weighting the 19 member states using 2020 population data. Source: Our World in Data, Eurostat, Birchstone Markets

Inflation is even more distorted than elsewhere

This year’s surge in eurozone inflation has been driven by the usual suspects; higher energy prices, supply bottlenecks and base effects. But there have also been some one‑off unique factors. In Germany, the reversal of a temporary VAT cut in place for H2 2020 and this year’s introduction of a carbon tax has pushed up on prices. As has the fact that the eurozone HICP measure has been reweighted to reflect shifts in pandemic spending patterns. Because of these upward influences, the annual rate of inflation has climbed to a 13-year high of 4.1%.

Although higher inflation could put some upward pressure on wage agreements, our assessment is that it will be contained by a significant amount of slack in European labour markets. Eurostat estimates that unmet demand for employment in Q2 was 14.5% of the extended labour force of the EU, with almost half of that (7.0%) accounted for by unemployed people. We are therefore of the view that inflation will begin to ease from the start of 2022 as German tax changes fall out, energy prices decline and supply bottlenecks are resolved.

ECB in no hurry to normalise policy

After an 18‑month strategy review, the ECB’s Governing Council unveiled its new inflation target in July. It will now aim for HICP to be 2% over the medium‑term, dropping its previous goal for it to be “below, but close to, 2%”. It has accordingly updated its forward guidance that sets out three key conditions before interest rates begin to rise:

- Inflation must be at least 2% well ahead of the end of the ECB’s forecast horizon.

- Inflation must be at least 2% for the remainder of the ECB’s forecast horizon.

- Inflation must be advanced enough to be consistent with stabilising at 2% over the medium‑term.

Whilst the first condition for “lift‑off” has been met, the remaining two do not appear to have been as the recent surge in inflation is expected to be transitory. Given the high bar set by this guidance, economists do not anticipate that the Governing Council will raise rates until 2024. But markets take a very different view. They are betting on a 10 basis point hike for late 2022 to be followed by a further 30 basis points increase in 2023.

President Christine Lagarde has pushed back against this, stating it is “very unlikely” to raise rates next year and “nor anytime soon thereafter”. It remains to be seen who is right, but investors would do well to remember that the ECB has twice had its fingers burnt before. Under the leadership of inflation hawk Jean-Claude Trichet, it prematurely raised rates in 2009 and again in 2011 only to have to perform a sharp volte‑face. It will therefore exercise extreme caution to avoid making the same mistake a third time.

Elections will ensure fiscal faucets to remain open

Following the German federal election in September, a tripartite ‘traffic light’ coalition has been formed. This centre‑left alliance has earmarked billions of euros for infrastructure projects and to accelerate measures to protect the climate. Meanwhile, next year’s presidential election in France should see an extension of fiscal support by the incumbent Emmanuel Macron. Additionally, the EU’s €800bn recovery fund should funnel strong investment into southern states such as Italy, which will hold a presidential election in January.