2022

FX and Macroeconomic Outlook

3 Editorial

4 United Kingdom

Britain’s economy was sent back to the year 2002 after the first lockdown caused output to shrink by a quarter. After an initially stop‑start recovery, the early and swift vaccine rollout has enabled the rapid removal of restrictions. This has put GDP on the cusp of regaining its pre‑pandemic level. However, there are various headwinds that threaten to blow the recovery off course. Key amongst these is the new Omicron variant, which scientists fear could be more transmissible and vaccine‑resistant than the Delta strain.

7 United States

Often hailed as the “land of opportunity”, the US lived up to its reputation after becoming one of the first advanced economies to reach its pre‑pandemic level in Q2. Growth has now naturally begun to moderate, which will gain momentum in 2022 owing to a significant fiscal drag. Although Jerome Powell’s second term as Fed Chair has been all but confirmed, the policy outlook is somewhat uncertain given the emergence of Omicron. Meanwhile, the administration’s weak grip on Congress is set to slip further after the midterm elections, with Republicans likely to make gains in the House and the Senate.

8 Eurozone

In many ways, the European outlook is like other advanced economies. Strong growth this year is set to return closer to trend as the reopening boost fades, whilst high inflation should fall back as transitory supply‑demand imbalances ease. But a key differentiating factor is that rate hikes remain far off due to the outcome of ECB’s strategy review which has set a high bar for tightening. Also, varying vaccination rates mean the bloc is particularly susceptible to any risks posed by the new Omicron strain, bringing with it an increased likelihood of further lockdowns.

9 FX Outlook

Editorial

Some might say 2021 has been a year of rebound. Many parts of everyday life have started to return to normal but still slightly different. GDP is returning to pre‑pandemic levels. We’ve seen the coronavirus adapt, change and mutate, all the while allowing life to creep back to normality. We’ve seen sport bounce back, like the Olympic Games, just without the same audiences, and we’re all experiencing the new norm of work. Life is nearly the same as a pre Covid world, yet very different and we take solace that the importance of human relationships are having somewhat of a renaissance alongside the technological revolution.

It’s a great metaphor for the world of FX and treasury. We believe at Birchstone we’ve developed a proposition that at first glance is similar but, in many respects, very different to the rest. Bringing a fresh proposition including risk profiling and analysis, peer data and cash management services. If anything, what we’ve learnt during the pandemic is the importance of human interaction and the need for quality technology. We know we’re not alone in the evolution of our business and we continue to be proud to work with so many companies that have defied the odds and continue to prosper in relatively tough conditions.

As we say farewell to a tough year we look forward to the joys of a new year. As part of that we wanted to share our economic thinking and what to look out for in the year ahead. We are pleased to be partnering with George Brown to produce this year‑ahead outlook. He has several varied years’ experience as an economist covering numerous advanced economies and emerging markets. Prior to his most recent role at Investec, George held positions at the Confederation of British Industry, Deutsche Börse and Oxford Economics. He was our first choice to bring the economic detail we believe our clients need as they look ahead to 2022, delivered in a manner that we trust is easy to digest.

Introduction

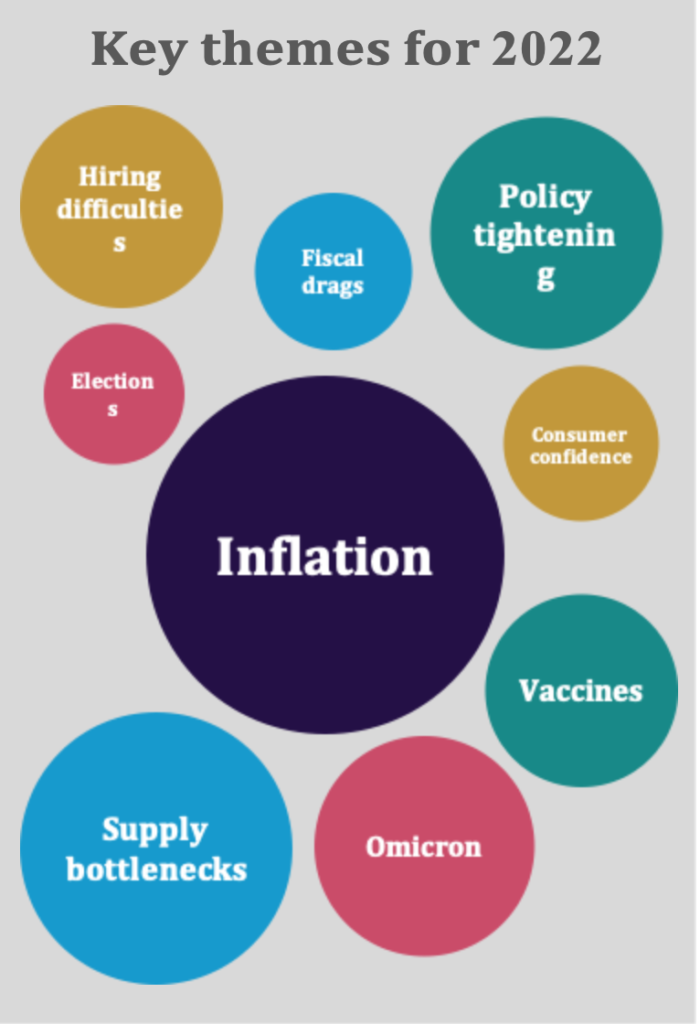

Like Marty McFly, the world economy was inadvertently sent back in time as lockdowns caused activity to shrink to its smallest size for decades. But the subsequent vaccine rollout has provided the 1.21 gigawatts needed to power the DeLorean’s flux capacitor and get back to the future. Several economies have now either regained their pre‑pandemic level or are on the cusp of doing so.

However, the speed of the recovery has caused supply‑demand imbalances to build, bringing with it the inflation of yesteryear. Though this should prove short‑lived, tight labour markets and rising inflation expectations could cause it to become embedded. For this reason, many central banks are poised to tighten policy to take out some ‘insurance’ against this threat.

But there is a risk that this is too little, too late. Determining how policy should be calibrated is challenging at the best of times, but even more so in the current circumstances. If central banks have miscalculated, they may need to apply the policy brakes more forcefully later, resulting in a greater correction to both growth and employment.

Another cause for concern is rising infection rates in Europe, particularly amidst the emergence of the new Omicron variant. If this proves to be more virulent and/or more vaccine‑resistant, hard times may lie ahead for 2022. It’s time to buckle up because where we’re going, we do need roads and it might be about to get bumpy.

United Kingdom: Growing Pains

Britain’s economy was sent back to the year 2002 after the first lockdown caused output to shrink by a quarter. After an initially stop‑start recovery, the early and swift vaccine rollout has enabled the rapid removal of restrictions. This has put GDP on the cusp of regaining its pre‑pandemic level. However, there are various headwinds that threaten to blow the recovery off course. Key amongst these is the new Omicron variant, which scientists fear could be more transmissible and vaccine‑resistant than the Delta strain.

Britain’s economy is back on track, but challenges remain

Currently, UK GDP is just 0.6% smaller than it was before COVID-19. This gap should be eliminated around the turn of the year, provided that stringent restrictions aren’t re‑imposed. But the high rate of inoculation should ensure this will not be necessary. Over 80% of the UK population have received their second dose, whereas 1 in 4 have received a booster vaccination. Still, the emergence of the Omicron variant poses a notable threat. It will be weeks until we know how much of a risk it presents (i.e. compared to the Delta strain), but the imminent extension of ‘boosters’ to all adults should help to diminish this.

Beyond this, growth should continue to moderate in 2022 as the initial reopening boost fades further. A major headwind is set to be the persistent disruption to global supply chains. Bottlenecks have arisen as a broad‑based, robust recovery in global demand has caused congestion at ports, leading to delays in the delivery of goods. Further exacerbating this has been various virus‑related disruptions at major Asian ports and factories.

How long the disruption to global supply chains will last is uncertain. Anecdotal feedback collated by the Bank of England’s agency network suggests it could continue until at least mid-2022 and may even spillover into H2. A key factor here will be how quickly consumption rotates from goods and back towards services, as is how persistent the current challenges in filling vacant positions proves.

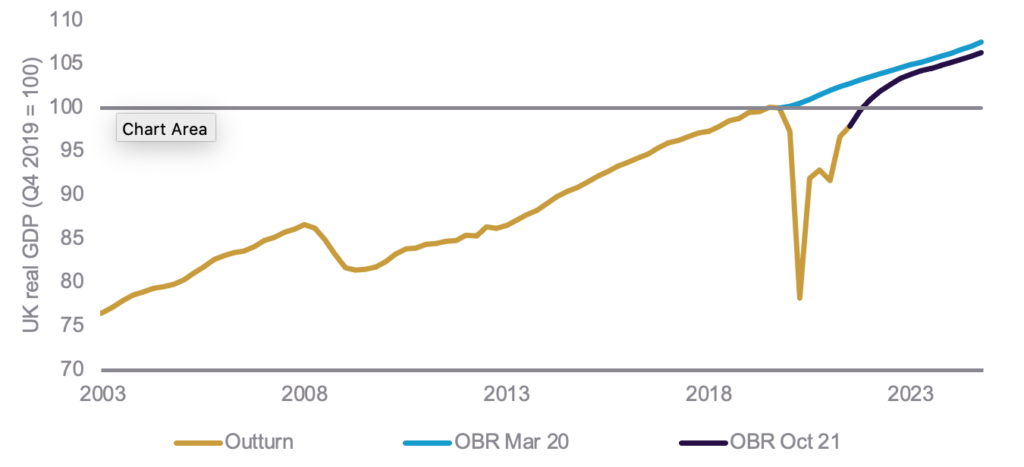

After a historic drop, is GDP Back to the Future?

Chart compares the March 2020 and October 2021 forecasts for UK GDP from the Office for Budget Responsibility. Source: ONS, OBR

Surveys show no let up in the current supply chain woes

Calculated as the difference between the supplier delivery times sub-component of the PMI and a counterfactual, cyclical measure of supplier delivery times based on the manufacturing output sub-index. Source: IMF, IHS Markit

These factors should result in a slower pace of UK GDP growth next year; the Bloomberg consensus is for it to moderate to 5.0% in 2022 after an expected 7.0% expansion in 2021. We judge that the balance of risks to the outlook is tilted to the downside, with the Omicron variant presenting a key source of uncertainty. Even so, the robustness of the recovery means the economy is now converging back to its pre‑pandemic path. The gap between the OBR’s latest GDP forecasts and what it published in March 2020 halves from around 4% this year to 2% in 2022 and again to just 1% in 2023.

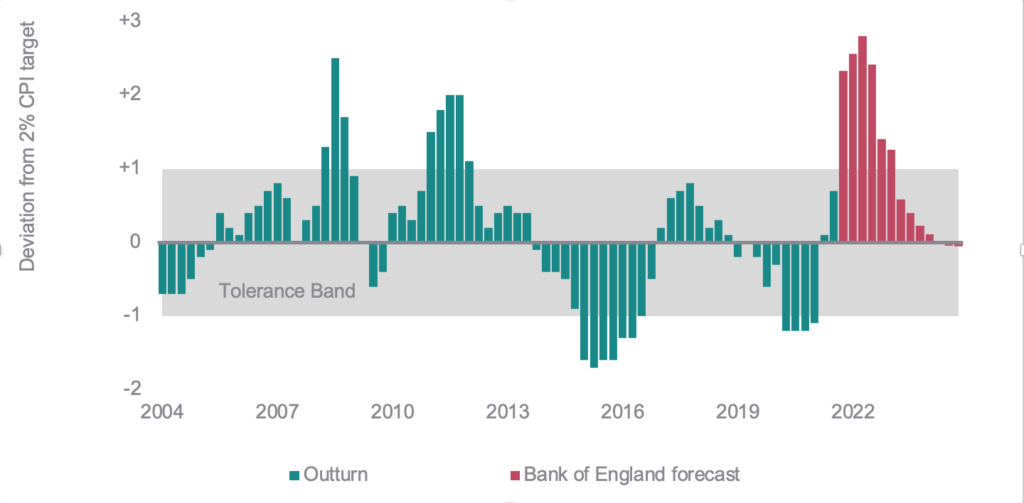

Transitory inflation could well prove persistent

Inflation is back with a vengeance in the UK; the annual rate of CPI reached a 10-year high of 4.2% in October, having started the year at a comparatively tame 0.7%. Its rapid ascent to more than double the Bank of England’s 2% target has come as a surprise to many, including the central bank itself. Back in February, it assumed it would currently be about 2%, but its most recent set of projections now see it peaking at around 5% in April 2022. So why has inflation confounded expectations so much?

- Energy prices Oil and gas prices have climbed on the back of the global recovery, with the latter also impacted by low stockpiles owing to supply disruptions.

- Supply chains Tradeable goods prices have risen sharply this year as supply struggled to meet the global rebound in demand, as have the costs of shipping them.

- Base effects Last year, the price of many goods and services declined. This has meant even modest price rises this year have had a large upward impact on CPI.

But these price pressures should prove transitory. Supply chain strains ought to ease, leading to something of a normalisation in international trade costs. Wholesale energy prices are also set to fall back as demand cools and supply constraints dissipate. Multiplying these disinflationary trends will be the ‘base effect’ flipping the other way in 2022 as falling prices are set against the rises seen throughout this year. For these reasons, the Bank of England estimates the annual rate of CPI will gradually ease over the second half of next year and will stand close to target by the end of 2023.

However, a cause for concern is whether second‑round effects emerge. For instance, consumers’ inflation expectations have drifted higher, with the year‑ahead measure of the Citi/YouGov survey climbing sharply over this year to now stand at the highest since 2008.

Inflation: here today, gone tomorrow?

The Governor of the Bank of England is required to write an explanatory letter to the Chancellor of the Exchequer if CPI inflation deviates more than 1 percentage point from the MPC’s 2% target. The shaded area on the chart illustrates this implicit ‘tolerance band’. Source: ONS, Bank of England

If expectations become ‘de‑anchored’, consumers may become more tolerant of price increases which then risks above‑target inflation becoming embedded. Workers may also demand higher wages to compensate for the squeeze on real incomes, which are more likely to be awarded by employers given the persistent difficulties in matching jobs with workers.

What will the final furlong for furlough mean for jobs?

Although the economy was hit hard by the pandemic, the labour market has been shielded by the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS). A total of 11.7mn jobs have been furloughed, including 8.9mn at its peak. As a result, the unemployment rate was 4.3% in Q3, just 0.3 percentage points higher than it was before the pandemic. However, there were still 1.1mn jobs covered by the scheme when it was wound up in September, of which 56% were fully furloughed.

This is concerning considering most restrictions have now been rolled back. As an illustration, if 0.5mn people find themselves out of work following the end of furlough, this would (other things equal) cause the unemployment rate to climb to 5.7%, the highest since early‑2015. But the evidence so far suggests there have not been widespread layoffs. Businesses report that less than 3% of furloughed employees were made redundant at the end of the scheme, whereas HMRC figures show a net rise of 160k employees enrolled onto PAYE in October. At the same time, the ratio of vacancies to unemployed people reached the highest level since figures began in 2001. Surveys also indicate that recruitment difficulties are becoming increasingly acute across a broad range of sectors and occupations. So why were so many workers still furloughed amidst such fierce competition for labour?

It is a complex puzzle and one that we do not currently have all the answers for. Firms hiring and hoarding workers in anticipation of higher demand and/or recruitment difficulties in 2022 is likely to be part of the story, as is lower immigration owing to a combination of Brexit and COVID‑19. We also suspect there is some permanency to the shift in spending patterns brought about by the pandemic, which will require workers to move across sectors and occupations in a meaningful way. While the flexibility and dynamism of the UK’s labour market should reconcile these issues in due course, for the meantime we expect hiring to remain challenging for much of next year.

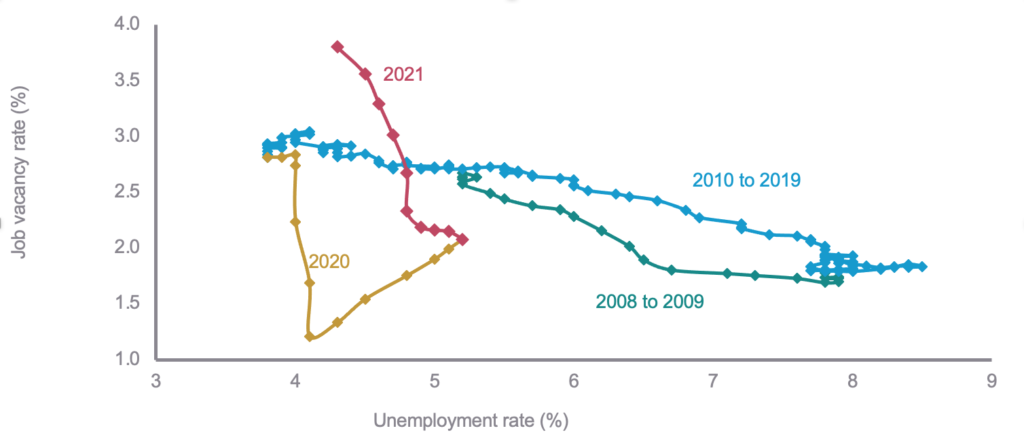

Labour market frictions re extremely elevated

Ordinarily when labour demand rises, unemployment falls and job vacancies increase. Beyond the furlough distortions of 2020, the sharp upward line for 2021 compared to the flatter profile of previous years suggests it has become far more difficult to fill open positions for the same level of unemployment. Source: ONS

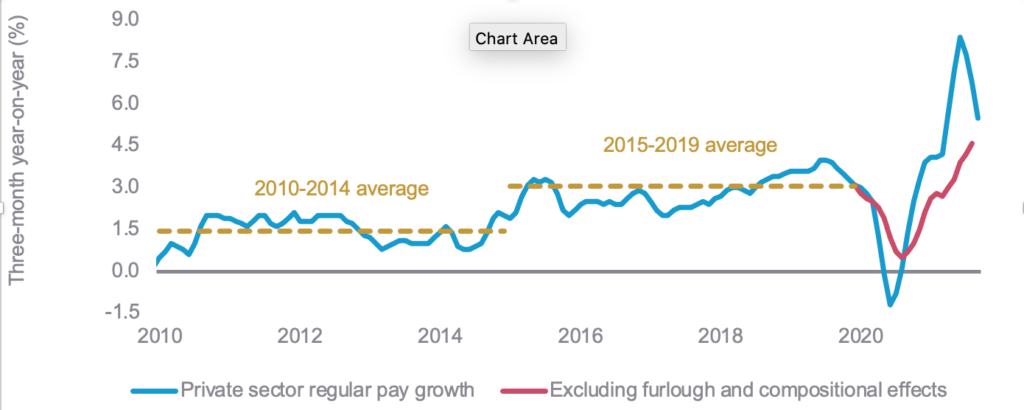

Wage growth is being distorted, but could prove sticky

Recently we have seen a moderation in wage growth, although it remains elevated by historical levels. But just like inflation, pay is being affected by transitory factors:

- Furlough effect Workers on the furlough scheme were paid 80% of their usual salary and rarely received a top‑up from their employer(s). This had the effect of pushing down on average wages in 2020.

- Compositional effect Many of the jobs lost as a result of the pandemic have generally been in lower‑paid occupations whereas better paying roles have proved more adaptable (e.g. remote working). This has had the effect of pushing up on average wages.

Estimates of underlying wage growth suggest that it is weaker than the headline series but is nevertheless running above its average for the past decade. One probable reason for this is that employees who faced a pay freeze in 2020 are being compensated with an above average wage increase this year. But it is also likely to be a symptom of the war for talent, as employers fight to hire and/or retain staff with skills in particularly high demand. Although we expect the pay pressures to ease over 2022, they are likely to remain somewhat elevated until the current labour market frictions can be ironed out.

Underlying wage growth is softer but above average

So‑called regular pay does not include bonuses paid out to employees, providing a clearer picture of underlying pay conditions. Source: ONS, Bank of England

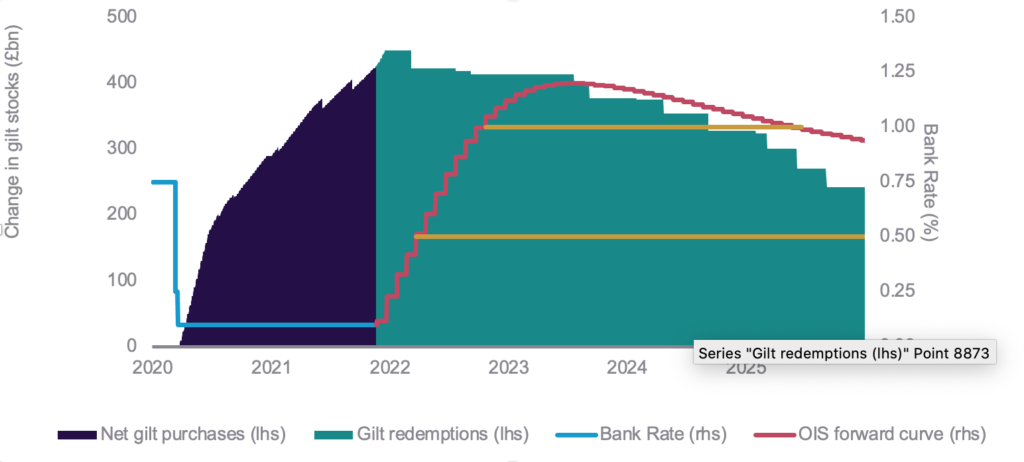

You can Bank on interest rates rising in 2022

Investors had expected the Bank of England’s MPC to raise borrowing costs in November to nip rising inflation

expectations in the bud. But instead a 7-2 majority of the committee elected to wait and see whether the furlough scheme would lead to a large rise in unemployment. Subsequent evidence suggests that it has not, but the official labour market data is not scheduled to be released until the week of the 16 December decision. Providing this does not show anything more than a modest rise in unemployment, we suspect committee will sanction a rise in Bank Rate from 0.10% to 0.25%.

This is likely to be followed by further hikes in 2022 to take out additional insurance against the second‑round effects previously described. Consensus expectations are for Bank Rate to rise by 25 basis points at both the April and November meetings to place it at 0.75% by the end of the year. Money markets remain of the view that it should even reach 1.00%. While the difference between the two is not material, the latter could see the MPC take a more significant step towards policy normalisation.

However, the MPC has also signalled that it will consider actively selling its stock of purchased assets once Bank Rate reaches 1.00%, dependent upon economic circumstances at the time. If investors are right and economists are wrong, there could be greater degree of quantitative tightening (or QT) in 2022.

BoE as never done QT, that could change next year

The two gold lines on the chart denote the dates that markets are pricing in when Bank Rate will reach 0.50% and 1.00%. These are the respective levels at which the MPC will stop the reinvestment of maturing gilt assets and at which it will consider actively selling the stock. Source: Bank of England

Eurozone:

E C not B moved

In many ways, the European outlook is like other advanced economies. Strong growth this year is set to return closer to trend as the reopening boost fades, whilst high inflation should fall back as transitory supply‑demand imbalances ease. But a key differentiating factor is that rate hikes remain far off due to the outcome of ECB’s strategy review which has set a high bar for tightening. Also, varying vaccination rates mean the bloc is particularly susceptible to any risks posed by the new Omicron strain, bringing with it an increased likelihood of further lockdowns.

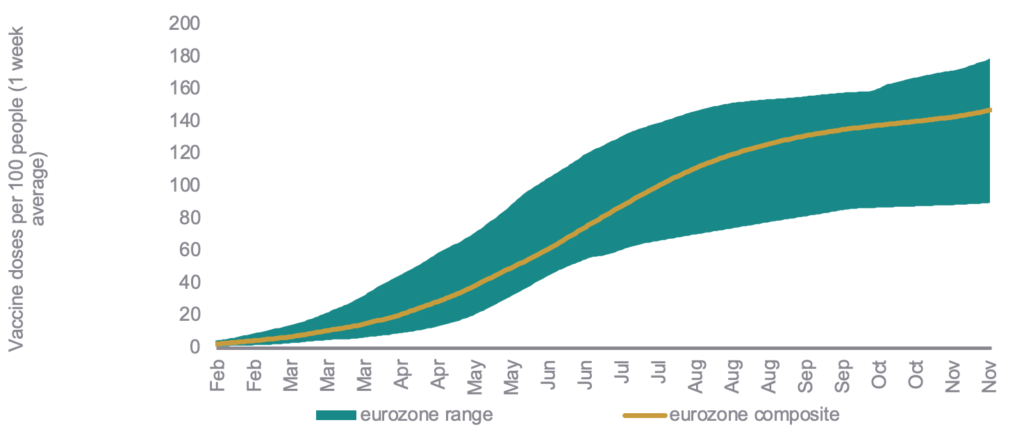

A winter of discontent is coming

After flatlining in Q1, the eurozone recovery has gained pace with sequential GDP growth exceeding 2% in both Q2 and Q3. A key factor underpinning this was the recovery in global trade, which provided a notable boost to the export‑oriented industrial sector, as was the rollout of vaccines that allowed governments to ease constraints on social activities. But beyond the healthy headline picture, southern states have lagged their northern neighbours. This largely reflects the significance of tourism to their economies, which was hampered by continued weakness in international travel in the summer.

While growth should go on to moderate next year, there will be a few supporting factors. An easing in supply bottlenecks would enable manufacturers to restock, whereas less stringent travel rules should boost tourism. However, low vaccination rates in some countries have caused another wave of cases to spread across the continent. This has led to a tightening of restrictions in several countries which has sparked large‑scale, violent protests. Forecasters look for growth to moderate from 5.1% this year to 4.2% in 2022. However, the emergence of the Omicron variant increases the likelihood of a widespread reimposition of restrictions that could dampen growth in late-2021 and early-2022.

Vaccination rates vary considerably in the eurozone

We construct the eurozone composite by weighting the 19 member states using 2020 population data. Source: Our World in Data, Eurostat, Birchstone Markets

Inflation is even more distorted than elsewhere

This year’s surge in eurozone inflation has been driven by the usual suspects; higher energy prices, supply bottlenecks and base effects. But there have also been some one‑off unique factors. In Germany, the reversal of a temporary VAT cut in place for H2 2020 and this year’s introduction of a carbon tax has pushed up on prices. As has the fact that the eurozone HICP measure has been reweighted to reflect shifts in pandemic spending patterns. Because of these upward influences, the annual rate of inflation has climbed to a 13-year high of 4.1%.

Although higher inflation could put some upward pressure on wage agreements, our assessment is that it will be contained by a significant amount of slack in European labour markets. Eurostat estimates that unmet demand for employment in Q2 was 14.5% of the extended labour force of the EU, with almost half of that (7.0%) accounted for by unemployed people. We are therefore of the view that inflation will begin to ease from the start of 2022 as German tax changes fall out, energy prices decline and supply bottlenecks are resolved.

ECB in no hurry to normalise policy

After an 18‑month strategy review, the ECB’s Governing Council unveiled its new inflation target in July. It will now aim for HICP to be 2% over the medium‑term, dropping its previous goal for it to be “below, but close to, 2%”. It has accordingly updated its forward guidance that sets out three key conditions before interest rates begin to rise:

- Inflation must be at least 2% well ahead of the end of the ECB’s forecast horizon.

- Inflation must be at least 2% for the remainder of the ECB’s forecast horizon.

- Inflation must be advanced enough to be consistent with stabilising at 2% over the medium‑term.

Whilst the first condition for “lift‑off” has been met, the remaining two do not appear to have been as the recent surge in inflation is expected to be transitory. Given the high bar set by this guidance, economists do not anticipate that the Governing Council will raise rates until 2024. But markets take a very different view. They are betting on a 10 basis point hike for late 2022 to be followed by a further 30 basis points increase in 2023.

President Christine Lagarde has pushed back against this, stating it is “very unlikely” to raise rates next year and “nor anytime soon thereafter”. It remains to be seen who is right, but investors would do well to remember that the ECB has twice had its fingers burnt before. Under the leadership of inflation hawk Jean-Claude Trichet, it prematurely raised rates in 2009 and again in 2011 only to have to perform a sharp volte‑face. It will therefore exercise extreme caution to avoid making the same mistake a third time.

Elections will ensure fiscal faucets to remain open

Following the German federal election in September, a tripartite ‘traffic light’ coalition has been formed. This centre‑left alliance has earmarked billions of euros for infrastructure projects and to accelerate measures to protect the climate. Meanwhile, next year’s presidential election in France should see an extension of fiscal support by the incumbent Emmanuel Macron. Additionally, the EU’s €800bn recovery fund should funnel strong investment into southern states such as Italy, which will hold a presidential election in January.

FX Outlook: Less Than Sterling

GBPUSD

It feels like we’ve been left at the altar numerous times in our belief that the pound will gather itself to make an assault on perceived fair value of 1.5000+, last seen the night before the Brexit vote back in 2016. Political events and the pandemic have created unforeseen circumstances that have not only hampered the UK’s growth but also significantly weakened the reputation of sterling, with no immediate signs of change as we move in to 2022. The likelihood that sterling will not totally shake the reputation it has been tagged with in the last year or two, of trading like an emerging market currency, leaves us resigned that the year to come could be another year of subdued demand for sterling.

Even if the risk is slightly weighted to the upside for GBP, considering the likely rapid return to growth and rising interest rates as inflation appears that it may settle in for longer than expected, it will still have to tackle a pretty resilient US dollar if it does want to ascend towards 1.4200, where GBPUSD peaked in 2021. The US economy has managed to sustain some momentum in the aftermath of COVID-19 and is gathering further support as the taper of their quantitative easing operations kicks in, laying the foundations for rate hikes in 2022.

For now, with global economic confidence still fragile, particularly in the face of the Omicron variant, the dollar is in vogue for it’s safe haven status and the likelihood is that interest rate hikes will creep up the agenda as the taper unfolds next year. Therefore, our expectation is that GBPUSD will remain in the doldrums of the 1.30’s with the most likely breakout of this northwards, only if the UK recovery remains on track and if UK monetary policy maintains a contractionary tone, with the market betting on future interest rate hikes in the UK.

GBPEUR

Whilst we’re, at best, cautiously optimistic on the sterling outlook for 2022, we believe the single currency will remain under pressure over the next 12 months which could pave the way for GBPEUR to break the pre-covid high of 1.2046. Whilst this is not certain given the UK backdrop we certainly expect GBPEUR to remain at elevated levels versus the average of 1.1400 over the last five years.

Currency markets are notoriously short-term in their thinking, right now the euro is sitting against the backdrop of a fourth wave, they have had negative rates for over seven years (which doesn’t look like changing any time soon) and the usual political fragmentation which has plagued confidence in the zone for the last ten years. Therefore, on paper the battle between GBP and EUR is a mismatch, particularly as we do expect the pound to gather some momentum from the recovery, from a position of being undervalued on a long term basis.

What could spoil the party for GBPEUR to remain at the top of the five year range where it currently finds itself in the 1.19’s? Well, to start, lets remember that the pound has not been the most reliable of late and Westminster is less predictable than ever, as is the shape and performance of an economy and workforce that has been ravaged by the pandemic. From the Eurozone, the political outlook, economic performance and the monetary policy expectations are all on the wrong side of positive, so there is room for improvement and therefore a positive swing in sentiment towards the single currency.

All considered, with our view that the pound will remain resilient if anything other than spectacular, we think GBPEUR has every chance of remaining at elevated levels and not returning to the single digits we saw in 2021.

We’re excited to announce that we will not be forecasting explicit currency rates next year. That’s right, we’ll give you market leading commentary and insights but we know our clients are tired of finger in the air forecasts.

Quite frankly, if we were in a position to give you forecasts that we truly could stand by, we would be running Birchstone from the beach in Barbados, with a beer in hand!

Instead, we’re launching something different. Deep data, scientific analysis and renowned academic expertise are coming together to allow us to launch the Birchstone Currency Valuation Model that will open up the black box of if the model believes a currency is overvalued or undervalued, giving our clients something simple and substantive to consider as part of rounded decisions on the FX risk management. We can’t wait to share more early next year.