Following a successful fight against inflation with sound policymaking from the central bank, utilising its hard currency reserves to support the nation, we’re back, baby!

Oh, sorry, those were my notes on Switzerland. My bad, let me find the UK.

Where are we at compared to our last review back in October?

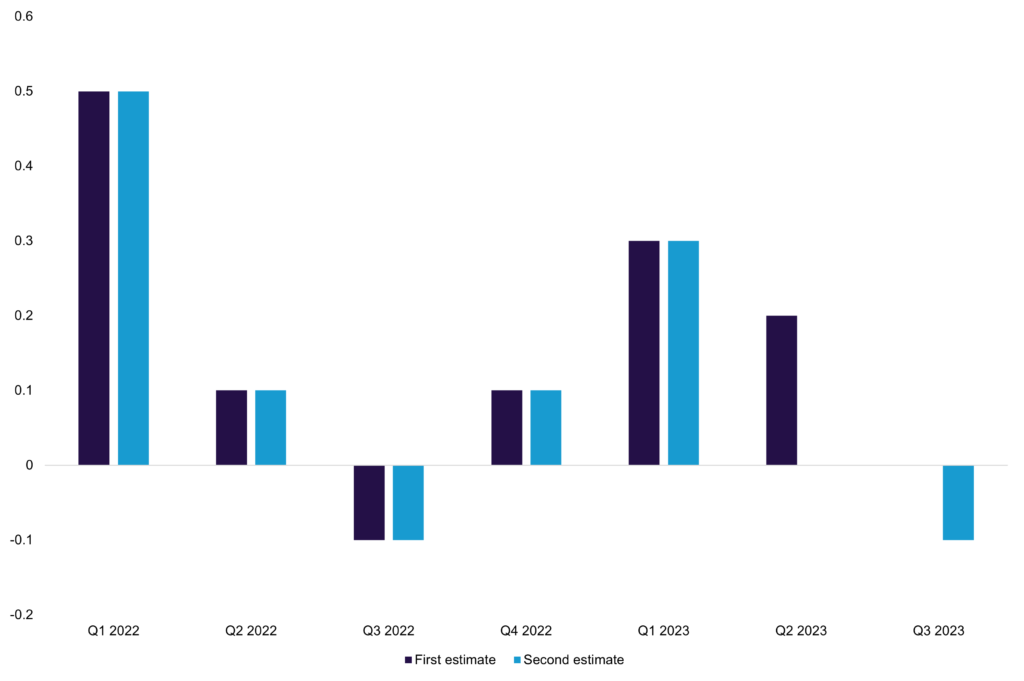

Well, I’ve got to say I feel like an idiot. I was a bit big-headed about some ONS revisions, which showed that the UK economy grew a bit more post-pandemic than previously understood, and I may have laughed at Germany now being on the bottom. Well, since then, we had the UK economy flatline in Q3 2023, which was bad enough, but then, as per the chart below, the ONS released new data (AGAIN!) on December 22nd (do they not let these guys out for Christmas?), revising away Q2 growth from +0.2% Q-o-Q to zero and the Q3 zero growth to a 0.1% contraction!

Things Were Already Rough; Now I Don’t Even Want To Look

UK – Quarterly Real GDP – ONS Estimates Of Q-o-Q Growth, Q3

Source: Various National Pollsters, JB Macro

I’d hate to be alarmist (mostly true), but what is happening at the ONS? In January 2023 they estimated average productivity growth over the pandemic (2020 and 2021) – at +5.0%, then revising this to -0.3% and admitting an error in the initial calculations.

“Consider this: the ONS signalled to policymakers that working from home was great for productivity, then reversed and said it was terrible.”

In the most notable instance of 2023, the ONS stopped publishing its labour force survey (LFS) data in October due to “quality concerns” as the response rate had plummeted, which sounds all wonkish and technical until we consider what this contains – the unemployment rate. The UK, an apparent world-class economy, stopped publishing its official unemployment rate.

So why am I ranting on this? Am I just some over-excitable nerd getting worked up about something minor? Well, yes, often; however, this one has serious real-world implications. To explain this, let’s have a quick fire on interest rates (wow, I know how to have fun).

Bank Rate?

5.25%.

High?

Yes, higher than before. In fact, it is higher than at any point since 2008.

Will it go higher?

Probably not. Three of the nine Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) members wanted it to go up 25 basis points (bps) in the December meeting. Since then, we’ve had economic revisions, and inflation has fallen further.

Will it come down soon?

It won’t be in Q1 2024, maybe in Q2 and Q3, most likely. And only gradually in Q3. Don’t expect a figure in the 3 percent before 2025.

Inflation is coming down; why won’t it get cut sooner and more materially?

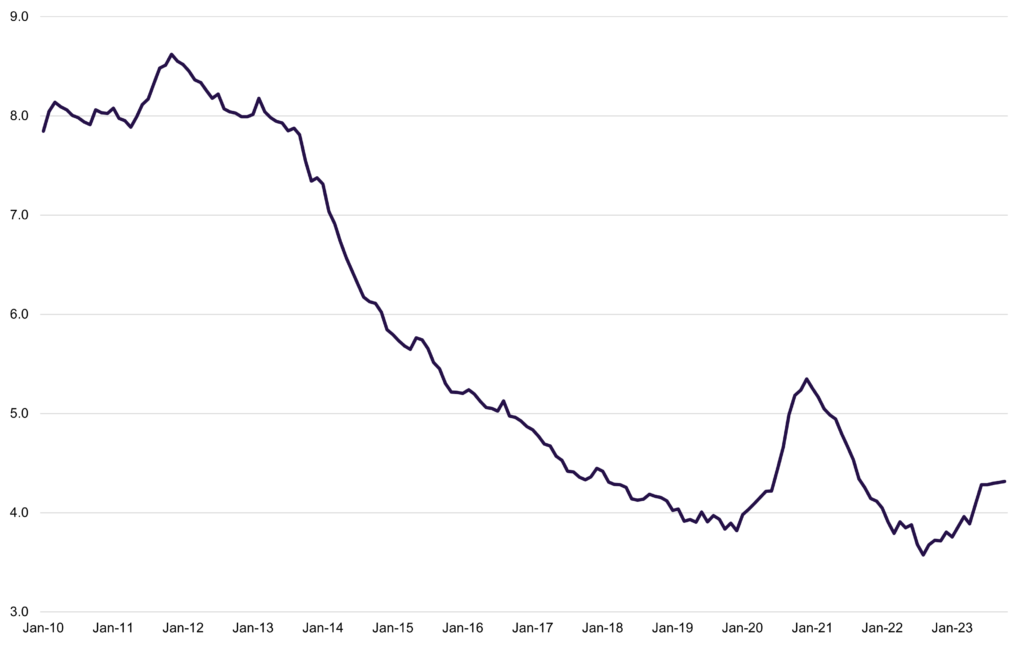

The labour market is still too strong, and there are fears of wages remaining too high and becoming inflationary. Makes sense. Wait, did we not just say the data is inconsistent? Yep, and even the MPC highlighted it was wary of this.

So, we’re at an interesting point. The policy must remain restrictive to loosen an overly tight labour market, but the data is uncertain. I won’t claim that the MPC is flying blind on the labour market – they have lots of data on hiring (itself not without faults), unemployment claimant data, HMRC PAYE data, and their new fancy experimental data – but they have lost a core part of the toolkit.

“Experimental Data” – Shows Unemployment On The Rise

UK – ONS Experimental Unemployment Data, SA, Rate, 16-64, 3MMA

Source: ONS, JB Macro

“Let’s try to piece all this together and get a grip on where the economy is, where it is heading, and the impact on rates.”

Starting with establishing how things look right now… and you know what, Q4 looked pretty OK! The economy might even have grown! The S&P Global UK composite PMI expanded through the quarter, coming in at 52.1 in December, above the 50.0 mark, consistent with expansion in activity and above October’s low of 48.7. The services PMI soared from 49.5 in October to 53.4 in December – important because services are around 80% of the economy – although the manufacturing PMI remained far below 50.0 at 46.2. At the same time, consumer confidence bounced (per GfK), with a significant improvement in the major purchase’s subcomponent.

With our base set, let’s look ahead. Some of this confidence will surely carry over into early 2024; however, I’ve got to say I reckon the outlook will deteriorate rapidly from here. It looks pretty rubbish. It’s not a crisis, but it’s definitely rubbish.

The core thesis here is that the bulk of the hiking cycle from the BoE has not filtered through to the economy yet, and the labour market tightness, which is driving all the fear of inflation, is, at best, transitory and, at worst, going to be revised away.

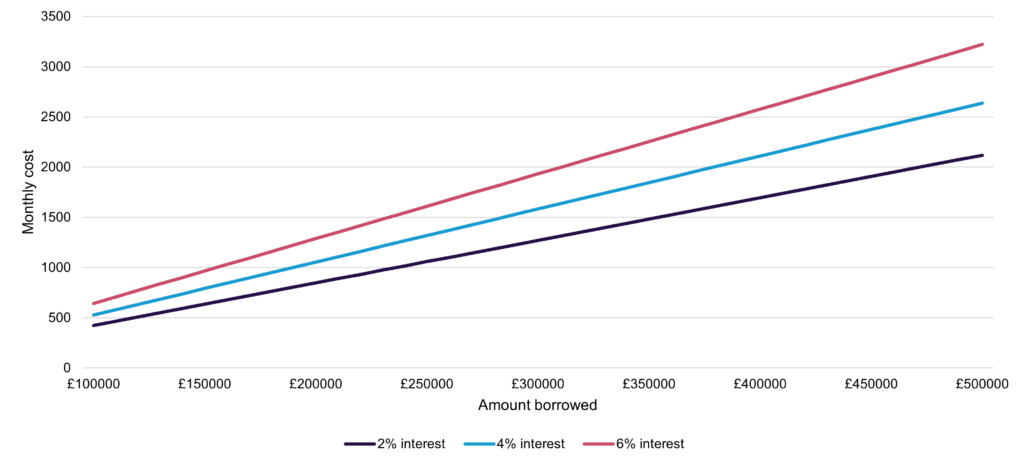

On the credit situation. Let’s dive into some figures. 27% of households are mortgaged, 37% own their houses outright. Of those 27%, around half have had fixed rates roll over to variable, so 13.5% of households have been affected by higher interest rate costs in terms of mortgages. The rest, primarily renters, have been affected, but not nearly to the same extent. Private rents were up 6.2% Y-o-Y as of November; however, there was no jump in average rents in line with inflation over 2020-22, and wage growth is just about keeping pace with rent gains (having outpaced it for the last few years).

A Painful Jump

UK – ONS Calculations For Monthly Mortgage Payment At Different Mortgage Interest Rates

Note: Assumes 25 year repayment period. Source: ONS, JB Macro

Looking ahead, the ONS estimates that 0.88mn fixed-rate mortgages will need renewing in the first three quarters of 2024, a total of 8.5mn mortgages (UK Finance figure). This means more households will be kicked into the higher payment brackets, and interest payments will rise even as fixed-rate products get marginally cheaper on the back of a recent repricing lower of swaps (which banks use to offset rate risk on mortgages). Business credit is also entering a challenging period, with BoE estimates showing that almost all the value of the corporate credit extended since 2008 is listed debt (bonds), which are typically fixed rates, with many needing to be refinanced over 2024/25/26.

“To spell it out simply, more households and businesses will be borrowing at higher rates in 2024 than in 2023, and this will again worsen in 2025, even if rates come down. This = bad.”

Bad for the ability to repay debt and bad for domestic demand. And before you say it, this dynamic looks set to be in play just about everywhere. That means the outlook for exports is also pretty rubbish, so we can’t rely on external demand to pull us out of the rump.

And now I want to bring in another element, and please, I ask, don’t burn me at the stake… Money supply. If you’re not familiar, there was a big focus in the 1980s on controlling inflation by restricting money supply – so-called monetarism – which pretty much failed, and the policy advocates went a long way to admit it (even Milton Friedman). The apparent fad spent decades in hiding thereafter. However, there is a clear reason to believe that the burst of inflation in the pandemic was due to a massive expansion in the money supply without an expansion in the supply of goods and services (more money + same goods & services = higher prices). Policymakers ignored this, and we had UK inflation over 10%. End of story. Or not quite.

While we ignored the money supply on the way up, surely we learned our lesson and won’t fall for the same error on the way down? Well, money supply is collapsing, shrinking more than 10% Y-o-Y. This comes as the CPI index and wages have already caught up with the 2020s expansion in money, so the inflationary “monetary overhang” has disappeared. This has clear and tangible consequences for the real economy. For instance, a collapse in M1 money supply (as has happened) usually brings with it a collapse in mortgage approvals (as has not happened yet). Might this collapse in money supply bring about a disinflationary splurge? I guess what I am getting at is, are policymakers at the BoE sleeping on monetarism on the way back down as they did when it went up? Are we amid a policy debacle? To note, the upside surprise on the December CPI inflation print (4.0% y-o-y versus 3.9% in November) doesn’t change this – the threat of having overtightened remains very real.

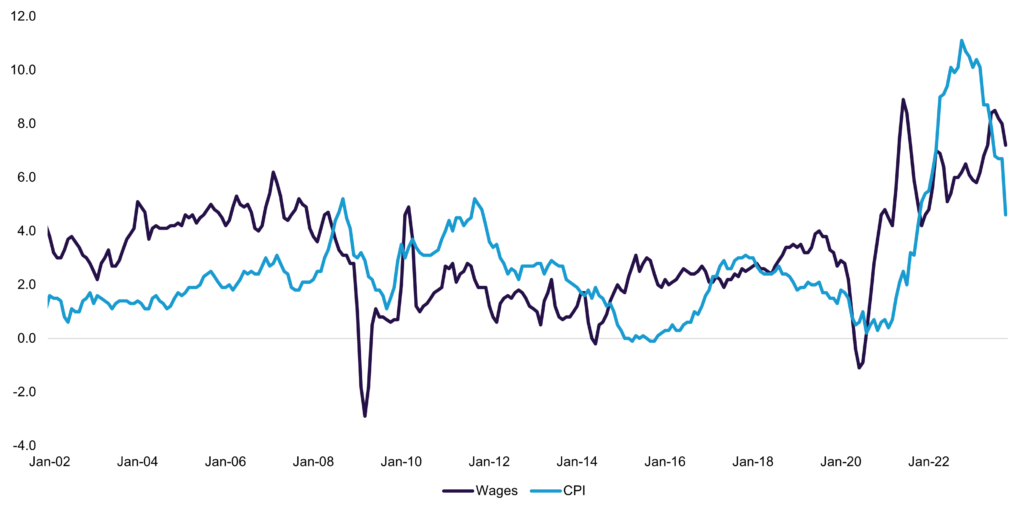

High Wage Gains – A Problem Or Transitory?

UK – Whole Economy Average Weekly Earnings, 3MMA, SA total pay, Vs CPI Inflation, Y-o-Y

Source: ONS, JB Macro

From here, the labour supply angle is easy. Given inconsistent data and the tendency for labour market data to get revised anyway, the understanding that the labour market is still tight may be incorrect. Strong wage gains may be completely transitory and collapse once the recent inflationary burst has worked through (wage gains often lag price gains). Even if the labour market is robust, it might deteriorate rapidly given:

- The credit outlook

- Rising business bankruptcies (presently up near 2008 levels)

- Already rapidly falling new hiring data

Not to mention, it is also hard to calibrate monetary policy to loosen the labour market but not collapse it when the policy rate is the main tool.

A Tough Gap To Bridge

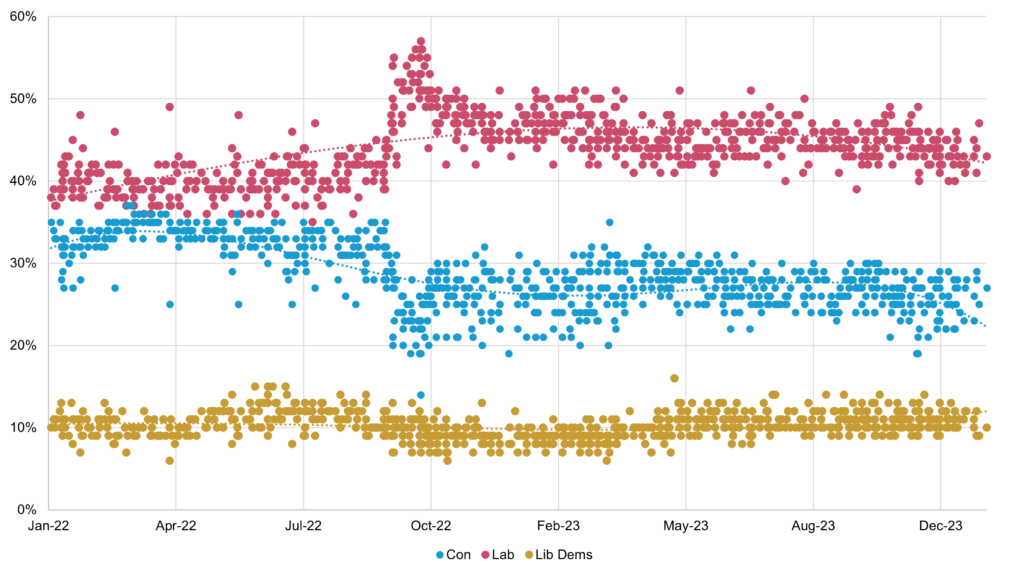

UK – Parliamentary Election Polling, % of voters

Source: Various National Pollsters, JB Macro

This gives us a great backdrop for a UK election, which PM Sunak almost confirmed would come in H2 2024. A May election is not entirely off the cards, but we’ll probably head to the polls in October. The most notable event of the last three months was the cabinet reshuffle, which saw Braverman booted out and ex-PM David Cameron brought in. It sounds to me like a tilt back to the centre after trying out the right wing and the public not liking it. Anyway, does it change anything? Not in my book.

Labour is still well ahead in the polls and most likely to win an absolute majority or a plurality. Braverman was probably still fairly popular in the North, and the pivot to the centre may lose some votes there. At the same time, it appears unlikely that the largely Conservative voting London Commuter belt – who are more likely to be of the One Nation Tory brand – will be as supportive of the party and pretend that the whole temporary pivot to the right – besides Johnson and Truss – did not happen.

So, what does this all mean for corporates?

Well, inflation looks set to be much less of a problem going forward. Absent a major supply shock – such as a more prolonged and pronounced version of the present shipping disruptions through the Suez Canal – input inflation looks set to be much lower. Even if we see a supply shock, it is unlikely to signal a return to high embedded inflation as we won’t see the same circumstances that led to high demand-driven inflation in 2020. The easier input cost narrative is already pretty evident in the producer price index (PPI), which is coming in negative (i.e. deflation) in Y-o-Y terms. An easing labour market should also limit input cost inflation from wage gains. The biggest concerns through 2024 will be the impact of debt rollovers onto higher rates, which will hit bottom lines and likely deter fixed investment. The poor demand outlook will also limit growth opportunities.

Elections typically offer a bout of uncertainty for businesses on the policy outlook. Still, given the pivot to the centre from both the Conservatives and Labour (versus mid-2023 for the former and versus under Corbyn for the latter), there should be some sense of continuity. It appears unlikely that Labour would roll back the Tory move to make full expensing tax relief permanent, and both parties look set to remove red tape and implement supply-side reform, for instance, in streamlining construction planning permission processes. Given the need to tighten fiscal accounts after the election, neither party would have space to do anything drastic.

On a more positive note, those firms that maintain decent levels of investment, specifically in tech, may benefit from new technologies such as AI. The jury is still out as to whether AI will be the productivity boon it is panned out to be. I firmly believe that even if productivity isn’t improved and output volumes stay the same, the firms that utilise AI will ultimately produce better products and have a more attractive value prop than competitors. The outlook is tough, but as usual, there are plenty of opportunities for those who position themselves well.

In the midst of this, the outlook for the GBP is mixed. Yields will be a big driver of the short-term price moves. On the assumption that markets have overpriced rate cuts in the US, the GBPUSD might fall (weaker GBP) as these expectations are pared back. It seems unrealistic that there will be a big discrepancy between the Fed and BoE cutting cycles. While yields induce some volatility and short-term downside, the trade outlook points to strength for the GBP in the medium term as a slightly worse economic outlook in the UK hits imports worse than the marginally better (but still poor) outlook overseas hits exports.

Contributors

James Bennett

Guest Economist

Views expressed in this article are by James Bennett, JB Macro, guest Macroeconomist.